The Love-Hate Relationship with Public Access to Court Records a/k/a PACER

PACER is a one stop tool for court searches. You can find cases. Then, you can dig into the case records for more information

In nearly every research project we perform, we point our browser to https://pcl.uscourts.gov. This is the URL for PACER. PACER stands for Public Access to Court Records. Now, when they say public, they mean those who sign up for an account, and when they say access, they mean if you pay the requisite fees. Court records mean the United States District Courts, the United States Bankruptcy Courts, and the federal Appellate Courts. PACER is the primary source we use for federal civil and criminal litigation searches and bankruptcy searches. It is not the sole source we use for litigation searches. We also have to search in other ways for state litigation records, which represents its own set of hurdles and issues, but today, let’s focus on PACER and why we love and hate it.

We love PACER most because we love court records or litigation searching. Legal proceedings are one of the key sources of information when doing background research. As I noted before, we track down court records for two reasons:

1. The records themselves speak to character and reputation – financial distress, sexual harassment, criminal conduct, these can all be determined from court records – if there was litigation. Hell, does the party like to sue? This is also invaluable information in assessing background.

2. The documents filed in connection with litigation, such as the complaint and other pleadings, transcripts, any exhibits, these provide a wealth of material that can be mined and otherwise delved into to learn about the parties being researched.

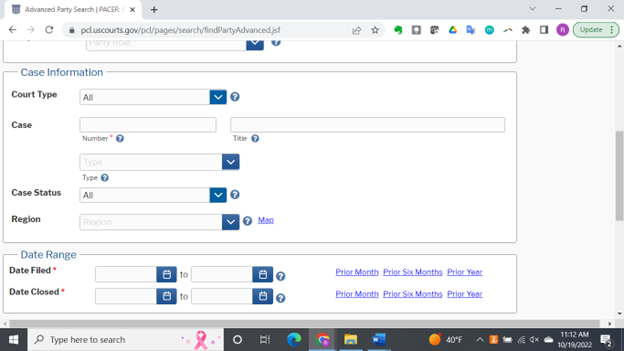

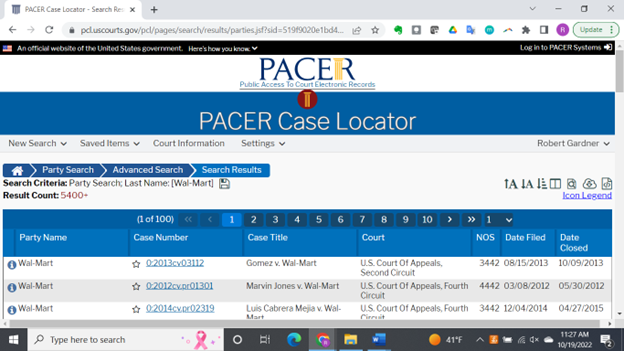

PACER is easy to use. The interface is clear and allows a variety of search options. The default search is national, which can often be a good thing. You can search every court, everywhere. Yet, that can produce enormous sets of potential results. So, PACER has advanced searching to control the results. We mostly use ‘Region’ from the drop-down function to limit the search results. You can narrow a search to a single District Court or broaden it to search an Appellate Circuit, but you can also choose to cover all the districts within a state. You can also sort results as a way of pinpointing; for instance, by looking only at open cases. We often find it very useful to sort cases by NOS, which stands for Nature of Suit. We may look for certain types of cases, like NOS 850, which refers to securities lawsuits, and ignore cases that are more mundane. Some screen shots from PACER are shown below.

You can search by cases (case number) or party, which includes plaintiff, defendant, and attorney

Searching by party

Some advanced search options:

Fields for sorting—every column can be used for sorting

PACER is a one stop tool for court searches. You can find cases. Then, you can dig into the case records for more information. For every case you find on PACER, there is an online docket sheet. The online docket sheet provides the basic details on a case and the parties involved. It also provides a chronological list of documents filed, and the docket sheet will tell you the status of the case. If the case is pending, the docket sheet will tell you the next action or hearing scheduled. The documents linked via the docket sheet will include the complaint, which lays out the basis for the lawsuit, as well as other pleadings like any counterclaims. There are motions, which effect and may end the litigation. Most motions are accompanied with a memorandum or brief in support of the motion. From a research perspective, the legal issues being argued may not matter, but these memorandum contain statement of facts and procedural histories, so they are excellent documents to pull to quickly learn about a case. Finally, if the case does go to trial, there will be documents related to that. Unless a document has been sealed by Court order (something happening too often these days), all the documents listed on the docket sheet can be obtained (for a price) on PACER.[1] To draw back to what was stated above, the documents serve two purposes. They tell you what has happened in the lawsuit, and they tell you about the parties in the lawsuit.

Brief interlude. What you get on PACER exceeds, almost always, what you can get via online access of other court records. Almost no state court system has such a robust system of docket sheet and related documents. With PACER, you get a docket sheet with the timeline and status of every case. With PACER you also get the underlying documents, which provide details on the lawsuit in question.

Fundamentally, PACER is a good thing. In practice, it can be exasperating. Moreover, there are design features that limit how it can be used. When we say exasperating, we do not mean that’s the most common complaint you hear about PACER. That is the paradox over calling something public access when it is only accessible if you pay for it. It is fashionable for journalists, researchers, and others who use PACER to gripe over the price. PACER is not the only online source of court records that charges for information. We just looked at some people in Utah. Had to pay for court searches. Colorado, Los Angeles County are a couple of other places we have to pay to get access to court records. A criminal record check in New York costs $98 ($95 + $3 in credit card fees). In the scheme of things, the cost of PACER is not a big deal. Although, to be warned, certain large files, especially transcripts, can be costly, as in ~$100 per file to download, but it’s rare that those files need to be downloaded. And it’s not the cost that bothers me.

What is more bothersome: the instability of PACER. Too often, you enter the name, get results, and then poof, it’s gone. For no known reason, searches will have to be done several times before it “sticks” on your computer screen. Same when you re-sort the results. It often takes a few tries to get it as you want. And to be able to move on to the next screen.

The clunkiness and instability are annoying. PACER fails in functionality in a few other ways. One is rather clerical in nature and could be alleviated and the other is the fault of the system. First, it’s the docket sheets. They note everything but not always in a way that helps. Here’s a quick example:

We often do work regarding expert witnesses. We will identify cases where the expert has testified or has been proposed as an expert. We then go to PACER to find documents related to the expert testimony. We want to find documents related to the experts including their biographies and their expert reports. Of course, we are looking for “Daubert[2]” challenges to the expert and any documents/opinions that disparage the expert. This is often easier said than done because often there is usually no specific item in the docket that says “expert” or “Daubert.” Often it will be lumped into other motions or given a general heading like “motion in limine.” By not adequately or properly labeling the documents in the docket sheet, it takes much more time and expense to review the records. There is no reason docket sheets cannot be better labeled.

Then, there is the problem that documents within PACER, all those juicy details, are not searchable. You cannot know what is inside a document until you download ($$) and look at it. This also means that you cannot find reference to a person or company within a litigation filing unless they were the plaintiff or defendant, one of the parties to the case. Wouldn’t it be great to get on PACER and search on other people who are involved, like to look for an expert witness name to find all the times he or she testified. Or any witness. Did they testify before. Look at this case that we lucked in to:

In looking at an individual’s background, we found a document that listed his employer. It was only interesting because this employer was not otherwise listed in materials on the subject, like the subject’s LinkedIn. This caused us to poke around a bit to find out who was this mystery employer. Because PACER is so easy to access, we ran the mystery company. We found a lawsuit involving both the mystery company and another company in the same industry as our client. This got us intrigued enough to go to the case documents. What we found was a matter where the subject of our research was not named as a party but was otherwise described as participating in a scheme to undermine his then employer by setting up a competing business. We only got to this document because of our Spidey sense and curiosity.

To put more succinctly, we found a case on PACER that contained negative information on the party being researched, but we did not, and could not, have found it had we searched his name on PACER.

There is a hack. Certain documents contained in PACER are otherwise published in a way that is fully searchable. We’re talking various orders and opinions issued by federal and appellate judges. These can be found on paid services like Lexis and Westlaw, and they can be found open-source, best these days via Google Scholar Case Law. these services make the documents fully searchable; free text searching, which means you can search on any word within the document, It is worthwhile to search published decisions, not looking for case law and precedent but for the odd chance your research subject shows up in a matter where he or she is not the named party. Still, many of the documents we want to examine are not the opinions and orders. We rue that they are not full text searchable.

PACER makes itself hard to use, sometimes because the dockets are not fully labeled; other times for no apparent reason. Finally, PACER could be even more useful if the actual documents within PACER were as searchable as the indices. Hence, the love-hate relationship.

[1] The oldest cases on PACER do not have any available online documents

[2] Daubert refers to Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993), a Supreme Court case that set the standard for excepting expert witnesses. In the parlance, “to Daubert” is to go after an expert’s credentials and to be “Daubert’d” is to be rejected by the trial court.